Without any doubt, octopuses are the smartest invertebrates. They have amazing features such as using their tentacles for sensing the environment that they are in or being able to change their skin color to protect themselves (camouflage) and many more.

As they evolved and lost their protective shells, octopuses developed clever ways to defend themselves. Today, their tentacles are almost more useful than their eyes, allowing them to sense their surroundings with precision.

“The three main parts of the octopus nervous system are the brain, the optic lobes, and the highly elaborated arm nervous system. Significantly, the arm nervous system contains three-fifths of the octopus’s neurons.” Writes in an article published in 2022.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8988249/#:~:text=The%20three%20main%20parts%20of,fifths%20of%20the%20octopus’s%20neurons.

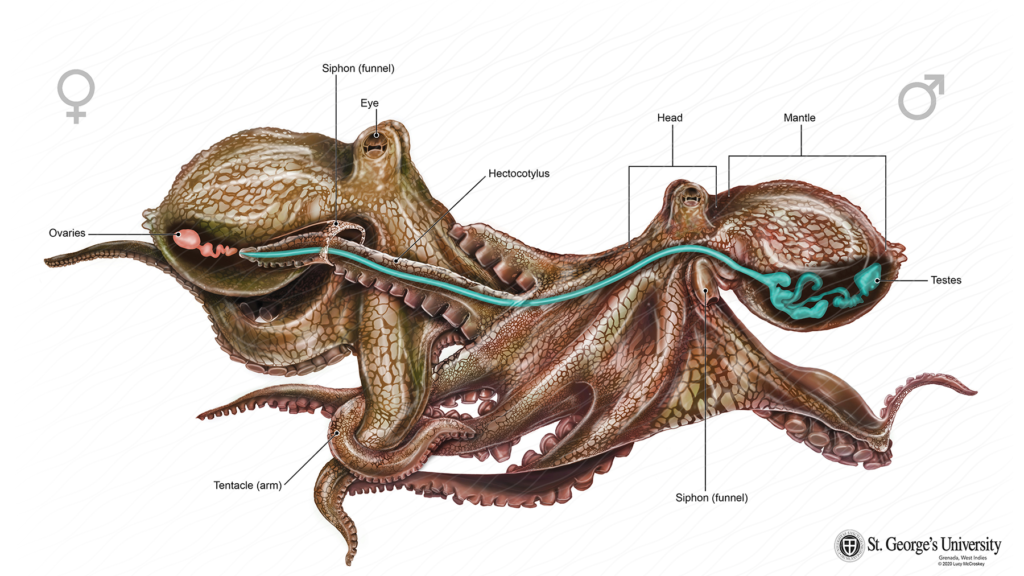

Of course, there is more to learn about their intelligence, but today I want to focus on their reproduction mechanism. Male and female octopuses look very similar, but the male has one specialized arm for mating.

The modified arm is called the hectocotylus, which is about 3 feet (1 meter) long and holds rows of sperm. A male’s hectocotylus arm is shorter than the others (and of course the most important of all the arms), so they usually protect it, keeping it curled up to avoid drawing attention to it.

Also, the hectocotylus doesn’t have chromatophores like the rest of the body, so this appendage is bright white.

Depending on the species, he will either approach a receptive female and insert the arm into her oviduct or take off the arm and give it to her to store in her mantle for later. In the latter scenario, the female keeps the arm until she lays her eggs, at which time she takes the arm out and spreads the sperm over her eggs to fertilize them.

Male Octopuses Face Some Dangers: Sexual Cannibalism

Sexual cannibalism is actually rare in the animal kingdom. Although cannibalism is not uncommon in cephalopods, a study reported the first documented case of sexual cannibalism. A large female Octopus cyanea was observed continuously for 2.5 days in Palau, Micronesia, when she was out of her den. On the second day, a small male followed and mated her 13 times during 3.5 h while she continued to forage over a 70 m distance. After the 12th mating, she aggressively chased a different small octopus that barely escaped by jetting, inking, and swimming upwards. Shortly thereafter, the original small male mated her a 13th time, but subsequently, she attacked and suffocated him and spent 2 days cannibalizing him in her den.

This sort of intraspecific aggression helps to explain several reports of octopuses mating out in the open, a behavior that may serve to allow the smaller mate to escape cannibalism.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10236240701661123

To avoid cannibalism, males have adapted certain behaviors:

- Make themselves appear larger

- Rise up to showcase large suckers near their beaks

- Flash bold color patterns across their bodies to convey their intentions

This behavior allows the females of Octopus vulgaris to obtain an extra contribution of energy to survive in the period of care of their offspring, a phase that lasts four months in which they eat nothing and need to live off their reserves.

After Mating

The female meticulously cares for her eggs until they hatch, forgoing food the entire time. She blows currents across the eggs to keep them clean and protects them from predators. The eggs might incubate anywhere from two to 10 months, depending on the species and the water temperature.

Once they hatch, they’re on their own – one source cites an estimated 1 percent survival rate for the giant Pacific octopus from hatchling to 10 millimeters. Depending on the species, some octopuses begin life as minuscule specks floating on the ocean’s surface that drift down upon reaching a larger size, while some start out a bit bigger on the ocean’s bottom. Little else is known about the early lives of octopuses.

If you think only the males are suffering, you are wrong

Octopuses are semelparous animals, which means they reproduce once and then they die. After a female octopus lays a clutch of eggs, she quits eating and wastes away; by the time the eggs hatch, she dies. In the later stages, some females in captivity even seem to intentionally speed along the death spiral, banging into the sides of the tank, tearing off pieces of skin, or eating the tips of their own tentacles.

Why is this happening?

Scientists have known that the animal’s optic glands are responsible for this behavior. When the glands are removed, the octopuses resume eating and live months longer. But just how these glands trigger the animal’s gruesome death has been a mystery.

Now, in a new study published in Current Biology, researchers describe changes to a series of biochemical pathways that happen after mating and may be responsible for the animal’s self-destruction. One of these changes leads to an increase in the substance 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC), a precursor to cholesterol.

“We know cholesterol is important from a dietary perspective and within different signaling systems in the body too,” says Z. Yan Wang, a professor of psychology and biology at the University of Washington and lead author of the study, in a statement.“ It’s involved in everything from the flexibility of cell membranes to the production of stress hormones, but it was a big surprise to see it play a part in this life cycle process as well.”

“The important parallel here is that what we see in humans, as well as in octopuses, is that high levels of 7-DHC are associated with lethality and toxicity,” Wang tells New Scientist. “And that, to me, is really interesting, just because of how evolutionarily divergent these two animals are.”

Indeed, parenting is challenging, even in the octopus world. We wish them the best and look forward to the next chapter in understanding these fascinating creatures. Stay tuned for my next article!

Resources

https://octonation.com/how-do-octopus-mate/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/scientists-figure-out-why-female-octopuses-self-destruct-after-laying-eggs-180980088/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10236240701661123

https://biosciences.uchicago.edu/news/grim-final-days-mother-octopus

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8988249/#:~:text=The%20three%20main%20parts%20of,fifths%20of%20the%20octopus’s%20neurons.

very interesting!